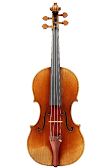

Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume

1798–1875Vuillaume was born into a family of violinmakers in Mirecourt, the premier center for the manufacture of string instruments in France, where he apprenticed to his father. In 1818, Vuillaume moved to Paris, initially to work for François Chanot (1788–1825). From 1821 to 1827, he joined the workshop of Nicolas Antoine Lété (1793–1843). By 1823, he had begun to affix his own labels to his instruments. After leaving Lété’s shop, Vuillaume opened a workshop of his own in 1827. His business success provided him with the means to move shop to a stately house at Rue Demours aux Ternes, where he continued to work for the rest of his life.

In the mid-19th century, Vuillaume dominated violin and bow making as well as the trade in string instruments throughout France and parts of Europe. His network extended to northern Italy, allowing him to provide the market with the best Italian instruments. Above all passionate collector and dealer Luigi Tarisio (around 1790 to 1854) regularly brought valuable instruments to Paris from 1827. Tarisio’s estate included no fewer than 24 Stradivari violins and 120 other instruments by Italian masters, most of which Vuillaume sold in Paris. Vuillaume was also a gifted restorer, equipping many instruments with new necks and bass bars in his workshop before putting them up for sale. He drew inspiration for his own instruments from the great Italian makers, producing mostly Stradivari and Guarneri replicas, but he also made instruments based on Amati’s or Maggini’s styles. Vuillaume applied a vibrant, reddish varnish. The fashion of the times called for shaded varnish to imitate the antique look of old instruments. Apart from these outstanding master instruments, Vuillaume also sold simpler brands mostly produced in Mirecourt with the mark “Stentor” or “Sainte Cécile.” Vuillaume also set standards in bowmaking. Many of the best French bowmakers, such as Peccatte or Voirin, worked for him at least for a while. Vuillaume’s efforts to enlarge resonance chambers were less successful. His so-called octobass – a huge, three-stringed double bass tuned one octave lower – did not catch on, nor did his viola model with its significantly wider upper and middle bouts.